Case Study Research in Music Education

Colleen Conway, University of Michigan; Kristen Pellegrino, University of Texas at San Antonio; Chad West, Ithaca College

Abstract

The term, “case study” is often used but less often cited and carefully described in music education research. The purpose of this paper is to clarify the use of the term “case study” in relation to music education research published in American journals. Following the model set forth by Lane (2011), we examined all case studies published in the Journal of Research in Music Education (JRME) and the Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education (CRME) in the time period 2007 – 2011, which included nine articles that state case study as the design. Our analysis considered the following aspects of case study research as derived from the case study literature: (a) appropriateness of design choice, (b) clarity of case study definition, (c) unit of analysis, (d) theoretical framework, (e) discussion of sampling, (f) depth of data sets, (g) description of analysis, and (h) trustworthiness or validity.

Conclusions suggest that researchers who are conducting qualitative case studies (a) clarify what kind of case study design they are employing and include citations and/or quotes to make this clear; (b) identify and define the single unit of analysis for their study, or, in the case of single-case (embedded) (Yin, 2009), the units of analysis; (c) consider including a theoretical framework in addition to the related literature section; (d) provide a discussion of purposeful sampling procedures used to choose/identify possible participant; (e) collect multiple forms of data, such as interviews, observations, background surveys, documents/artifacts, journals, audiovisual material, etc., (f) describe the analysis process and include discussion about within-case analysis, cross-case analysis, and/or assertions; and (g) describe multiple techniques used to contribute to trustworthiness or credibility (i.e. data triangulation, analyst triangulation, reflexive triangulation, member checks, adequate engagement in data collection, researcher’s position or reflexivity, peer review/examination, audit trail, rich, thick descriptions, and/or internal validity).

Case Study Research in Music Education

Part of the confusion surrounding case studies is that the process of conducting a case study is conflated with both the unit of study (the case) and the product of this type of investigation. Yin (1994)[1], for example, defines case study in terms of the research process….Stake (1995a)[2], however, focuses on trying to pinpoint the unit of study—the case. (Merriam, 1998, p. 27)

The above uses of the term “case study” to which Merriam referred are taken from the context of case study as a research design. One can see that there is confusion with the use of the term even within the same context—the process and product of conducting a type of research (case study research). This confusion is compounded when we consider that the term “case ” is also often used within music education to refer to an illustrative narrative designed for educational problem solving and critical reflection practice (Abrahams & Head, 2005; Atterbury & Richardson, 1995; Bailey, 2000; Brinson, 1996; Conway, 1997, 1999a/b; Hourigan, 2006; Lind, 2001; Richardson, 1997; Thaller, Finfrock, & Bononi, 1993). Scholars working with this type of “case” have discussed the following: (a) a “teaching case, (b) the development of “casebooks,” and (c) “casework” as an instructional tool. Within music education, Richardson (1997) delineated such teaching cases: “The case studies used in methods classes are fictional narratives unlike research case studies resulting from data collection and analysis” (p. 17). Conway (1999a) further described such cases: “As practiced in teacher education, the case method of instruction includes a variety of approaches using cases or stories of teachers in real or fictional settings as prompts for students’ discussion and reflection” (p. 20). Here we see two uses of the term “case” within the same context (a teaching context rather than as a research design method), and presumably to describe the same construct, both used in slightly different ways. One researcher used the term “case study” while the other used the term “case method.” Further, both scholars offered slightly different definitions of the terms to which they were referring (i.e., whether they are developed from fictional narrative—or real situations—or both).

Within the Journal of Research in Music Education (JRME), we found use of the term “case study” in two titles of articles that are not case study design but are using the term “case” to define the sample. Madsen and Hancock’s (2002) “Support for Music Education: A Case Study of Issues Concerning Teaching Retention and Attrition” was a quantitative survey. More recently Matsunobu’s (2011) “Spirituality as a Universal Experience of Music: A Case Study of North American’s Approaches to Japanese Music” was an ethnographic investigation. In both instances, it is unclear as to exactly how the author is using the term “case study”.

The purpose of this paper is to clarify the use of the term “case study” in relation to music education research published in American journals. Although intermittent, there are models for a discussion of research methods within music education research journals (Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 123, 130, 131; Bresler, 1992; Cain, 2008; Conway, 2008; Krueger, 1987; West, in press). Lane (2011) analyzed qualitative research appearing in the Journal of Research in Music Education and the Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education and reported that case study was the most well used qualitative research strategy in music education. Thus, it seemed to us to be timely to carefully consider its use in our field.

General Characteristics of Case Study

Merriam (1998, 2009) defined three important characteristics of case studies: particularistic, descriptive, and heuristic. The first characteristic of case study is particularistic, meaning that the study focuses on a particular phenomenon. [3]

The case itself is important for what it reveals about the phenomenon and for what it might represent. This specificity of focus makes it an especially good design for practical problems—for questions, situations, or puzzling occurrences arising from everyday practice. (2009, p. 43)

The second characteristic of case study is the “rich, thick description of the phenomenon under study” (p. 43). The last characteristic is the heuristic quality of case studies in that they explain the reasons for the problem, the background of the situation, what happened, and why. Case studies “can bring about the discovery of new meanings, extend the reader’s experience, or confirm what is known” (p. 44). What makes case studies in education unique “is their focus on questions, issues, and concerns broadly related to teaching and learning” (1998, p. 37).

The nine case studies examined for this article had many of these key qualitative characteristics outlined in the above section. However, the subtleties of “case study” research often make clarity difficult. The next section of this paper will highlight this confusion.

Case Study within Music Education

Following the model set forth by Lane (2011), we examined all case studies published in the Journal of Research in Music Education (JRME) and the Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education (CRME) in the time period 2007 – 2011 (the five years previous to Lane’s statement that case study was prevalent and previous to the start date of our work) which included nine articles that state case study as the design (Abramo, 2011; Chaffin, 2009; Conway, Eros, Pellegrino, & West, 2010; Conway & Holcomb, 2008; Gackle & Fung, 2009; Hourigan, 2009; Oare, 2008; Sindberg, 2007; Standerfer, 2008). As will be discussed in the conclusion, there may be other qualitative studies that meet the criteria for case study but if the author(s) did not state “case study” as the design, we did not include it in our analysis.

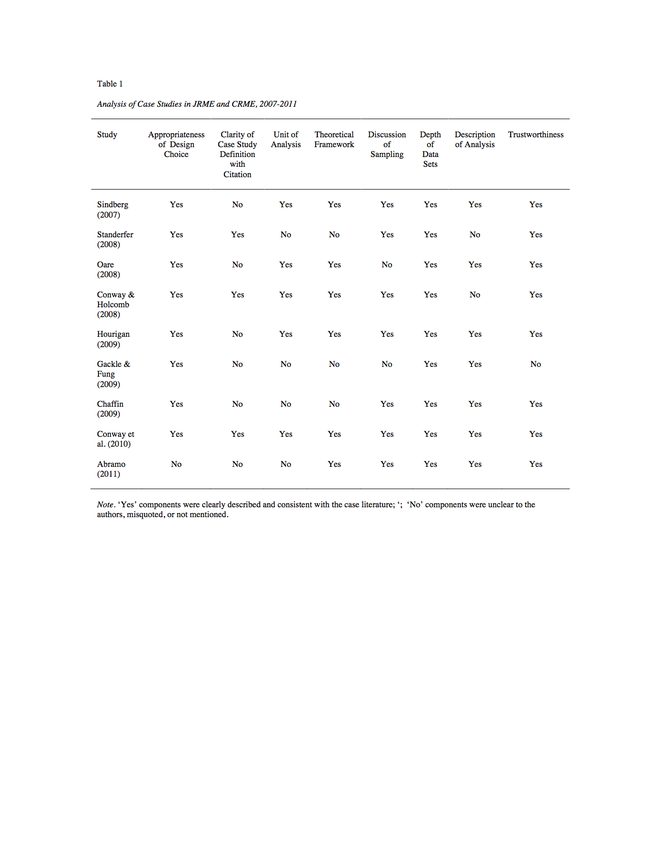

Our analysis considered the following aspects of case study research as derived from the case study literature: (a) appropriateness of design choice, (b) clarity of case study definition, (c) unit of analysis, (d) theoretical framework, (e) discussion of sampling, (f) depth of data sets, (g) description of analysis, and (h) trustworthiness or validity. Table 1 includes a summary of analysis. These studies will be refereed to throughout the next section of the paper. Please note that we are not trying to be critical of the work done by these scholars. We are only using the examples provided so we can all learn about the subtleties of case study work. Each of these studies makes an important contribution to the music education literature at large. Each aspect of case study research is discussed below with an example from the music education literature.

Appropriateness of Case Study Design

In this type of research, it is important to understand the perspectives of those involved in the phenomenon of interest, to uncover the complexity of human behavior in a contextual framework, and to present a holistic interpretation of what is happening (Merriam, 1998, p. 203).

Qualitative case studies, as in other qualitative designs, explore meanings and understandings of experiences. Using the researcher as the primary instrument of data collection and analysis, an inductive investigative strategy, the end product is richly descriptive (Merriam, 2009, p. 39). Merriam (1998) began her case definitions by identifying some key philosophical assumptions in qualitative research, such as the idea that qualitative research is based on the view that,

Reality is constructed by individuals interacting with their social worlds. Qualitative researchers are interested in understanding the meaning people have constructed, [italics in original] that is, how they make sense of their world and the experiences they have in the world…It is assumed that meaning is embedded in people’s experiences and that this meaning is mediated through the investigator’s own perceptions. (Merriam, 1998, p. 6)

Stake wrote that the purpose of case study design is to help the reader “gain a fresh apprehension of phenomena. New understandings emerge gradually from additional cases understood through the detail of personal and vicarious experience” (1995a, p. 42). Stake (1995b) wrote: “In qualitative case study, we seek greater understanding of the case. We want to appreciate the uniqueness and complexity, its embeddedness and interaction with its context” (p. 16). He also submitted (1995b) that case study is a way of studying something special, often centered on an issue. He defined issues as “problems about which people disagree, complicated problems within situations and contexts” (p. 133). Expanding on the constructivist view of knowledge, Stake explained:

In formal inquiry or in everyday experience, people construct the meaning of phenomena in relation to their perceptions of similarity, importance, implication. The emphasis here is on their perceptions. Even perceptions which are largely sensory…are greatly understood within the context of past experience. And with each interpretation, new knowledge is constructed. (p. 38)

Multiple authors have described how to determine if case study is an appropriate design for a qualitative research study (Creswell, 2007; Merriam, 2009; Yin, 2003, 2009). Creswell (2007) wrote that the first procedure for conducting a case study was determining whether “a case study approach is appropriate to the research problem. A case study is a good approach when the inquirer has clearly identifiable cases with boundaries and seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of the cases or a comparison of several cases” (p. 74). Yin (2003) suggested that case studies are preferred when ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions are being posed. Yin (2009) stated that case study is especially appropriate when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not “clearly evident” (p. 18). Gall, Gall, and Borg (2007) wrote similarly about case study, saying that it is the in-depth study of one or more instances of a phenomenon in its real-life context and that it reflects the perspective of the participants involved in the phenomena. Merriam (2009) believed that “The case study offers a means of investigating complex social units consisting of multiple variables of potential importance in understanding the phenomenon” (p. 50).

Music education studies. All nine studies from music education seemed to us to be appropriate for a case study approach. In the Abramo (2011) study it is unclear whether case study was really the design focus as the term only appears in the abstract and no case study criteria (i.e. type, unit of analysis, type of case analysis) was provided. Citations in the method section clarify ethnography, participant observation and interviewing techniques but no “case study” citations were included. Because there are so many different types of case studies, explicitly describing the case study definition and/or supporting it with citations is an important feature of case study design that is sometimes overlooked in research publications. It may be that calling this study ethnography or phenomenology better describes Abramo’s important contribution.

Clarity of Case Study Definition

Depending on the author, there are different categories of case studies (Creswell, 2007; Merriam, 1998, 2009; Yin, 2009). Merriam (1998, 2009) wrote about three types of case studies: descriptive, interpretive, and evaluative. Merriam differentiated between these types of case studies by focusing on the intent of the case study. Descriptive case studies describe the unit of analysis in detail, but do not attempt to interpret or evaluate. In an interpretive case study: “A case study researcher gathers as much information about the problem as possible with the intent of analyzing, interpreting, or theorizing about the phenomenon” (p. 38). Last, even though these case studies involve descriptions and explanations, the aim of an evaluative case study is to ultimately produce judgment. The focus of this type of study is well suited for evaluating an educational program or a school.

Creswell (2007) wrote about three types of case studies: single instrumental, collective or multiple, and intrinsic. Drawing on Stake (1995a), Creswell defined a single instrumental case study as when “the researcher focuses on an issue or concern, an then selects one bounded case to illustrate this issue” (p. 74). In a collective or multiple case study, multiple case studies are selected to examine and better understand the one issue or concern. Creswell pointed to Yin’s (2003) argument that this design has the “logic of replication, in which the inquirer replicates the procedures for each case” (p. 74). Intrinsic case study focuses “on the case itself (e.g., evaluating a program, or studying a student having difficulty…) because the case presents an unusual or unique situation” (p. 74).

Yin (2009) presented four categories of case study designs: single-case (holistic), single-case (embedded), multiple-case (holistic), and multiple-case, (embedded) (pp. 46-62). The difference between a holistic or embedded design, for Yin has to do with how many units of analysis are being examined. Holistic designs have a single unit of analysis whereas embedded designs have multiple units of analysis. He examined five reasons to choose single-case designs as determining whether the case is a critical case (used to test a theory), extreme or unique case, typical case, revelatory case (“when an investigator has an opportunity to observe and analyze a phenomenon previously inaccessible to social science inquiry,” p. 48), or longitudinal case (“studying the same case at two different points in time,” p. 49). The multiple-case design has the advantage of replication.

Music education studies. Overall, clarity of case study definition with citation is the least consistent aspect of case study research found in these music education studies. Within the music education literature, Hourigan (2009) used the term “particularistic case study” and stated:

A particularistic case study design was used in this study. Merriam (1998) defines a particularistic case study as research that “focuses on a particular situation, event, program or phenomenon” (p. 29). This study was phenomenological. It examined the structure of the lived experience of the participants…as they collaborated, interacted, and participated in a … (p. 154).

The Hourigan example provided important information and addressed many of the key case criteria discussed in this paper. The author stated the type of case study and included a quote from Merriam to support that choice. The author also stated the theoretical framework (phenomenology) and later in the article, provided an extensive discussion of how that framework was employed. However, upon careful examination of Merriam (1998) regarding case study, the quote that we find that directly addresses the term “particularistic” states: “The case study can be further defined by its special features. Qualitative case studies can be characterized as being particularistic, descriptive, and heuristic” (Merriam, 1998, p. 29). This quote addresses general features of all case studies, but does not identify “particularistic” as a type of case study. Rather, Merriam defines the three types of case studies discussed previously: descriptive, interpretive, and evaluative.

Chaffin (2009) used citations to support his design, sampling was carefully discussed, and the data set is deep. However, Chaffin (2009) also stated: “A particularistic case study design was used to obtain data from…” (p. 23). Like Hourigan, we believe that Chaffin may have misinterpreted Merriam (1998) with regard to “particularistic.” Gackle and Fung (2009) stated: “This was a qualitative case study using a participatory approach in which the researchers participated and collaborated in the study (Patton, 2002)” (p. 70). The authors discussed the participatory approach and provided citations to support that aspect of the design but there is no citation or definition for case study.

Unit of Analysis

An important feature of case studies is delimiting the object of study. This is done through defining the single case or unit of analysis to be studied. Merriam (2009) wrote:

Since it is the unit of analysis that determines whether a study is a case study, this type of qualitative research stands apart from the other types (of qualitative research), (which) are defined by the focus of the study, not the unit of analysis. By concentrating on a single phenomenon or entity (the case), the researcher aims to uncover the interaction of significant factors characteristic of the phenomenon. The case study focuses on holistic description and explanation. (pp. 42-43)

Music education studies. Within the nine studies examined, Standerfer (2008) stated: “A qualitative research design was used for this study of the participants’ perspectives and was based on a naturalistic paradigm (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The research design incorporated three case studies based on in-depth personal interviews with the teachers (Yin, 1994)…” (p. 78). In this example, the unit of analysis was not explicit, but can be inferred: “This study was designed to investigate influences on the teaching practices of three [Types of] music teachers who participated in the process of [Name] certification in music.” This delimits the investigation to “influences on the teaching practices” as opposed to their opinions of the certification program or how engaging in this process may influence their personal lives. However, it is not completely clear as to what is the unit of analysis or how the case is bound (Merriam, 2009) by time and space.

Conway, Eros, Pellegrino, and West (2010) stated: “This inquiry used a qualitative approach and employed a case study design (Merriam, 1998; Stake, 1995a, 1995b)…In this study, the single unit of analysis was the lived experience within the instrumental music education community” (p. 262). In this example the unit of analysis is carefully described and citations were used to clarify the use of the term, “case.”

Theoretical Framework

Merriam (1998) defined theoretical framework as “the lens through which you view the world” (p. 45). This includes concepts and theories from literature reviews and fields such as philosophy, psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Explicitly describing the theoretical framework is an important feature of case studies and lends credibility to studies. Scheib (2014) provided a comprehensive discussion of the many misunderstandings regarding the notion of a theoretical framework.

Music education studies. For our analysis, we simply documented whether authors stated a theoretical or conceptual framework or not. Just because an author did not explicitly write: “this was my theoretical framework,” does not mean that there was not a solid framework. However, we suggest that some sort of framework is so important for qualitative research that authors might wish to be quite explicit in labeling the framework. All nine papers included past research as a framework. The following authors did not provide an explicit framework beyond that: Oare (2008); Standerfer (2008); Gackle and Fung (2009); and Chaffin (2009). Sindberg (2007) identified aspects of Comprehensive Musicianship through Performance (CMP) as her framework. Conway and Holcolmb (2008) labeled and defined heuristics as the lens (p. 57). Hourigan (2009) provided an extensive discussion of phenomenology as the “Theoretical Framework” (p. 153). Conway et al. (2010) used the term “Conceptual Framework” (p. 261) and cited general teacher education socialization literature.

Discussion of Sampling

The validity of qualitative research with regard to sampling depends more on the richness of the case(s) studied and the observation and analysis of the researcher than on the size of the sample. Purposeful sampling allows the researcher to intentionally select information-rich, illuminative cases for in-depth study. Patton (2002) provided a comprehensive discussion of 16 variations of purposeful sampling strategies used in qualitative research. Common purposeful sampling strategies used in music education include: “typical case sampling” to “illustrate or highlight what is typical, normal, average” (p. 243); “critical case sampling” which “permits logical generalization and maximum application of information to other cases because if it’s true of this one case, it’s likely to be true of all other cases” (p. 243); and “extreme or deviant case sampling,” meaning “learning from unusual manifestations of the phenomenon intensely, but not extremely, for example, outstanding successes/notable failures” (p. 243).

Music education studies. Within the music education studies, Oare (2008) and Gackle and Fung (2009) provided no discussion of sampling. In both studies they were describing a single case, which seems to us to be the most important type of case study to justify with a discussion of sampling. All other authors provide some rationale as to how participants were chosen, with some being more detailed than others. Regardless of the sampling strategy used, researchers should justify why particular participants were chosen and how the reader should consider them in relation to others. We suggest that qualitative researchers be more transparent in their strategies for sampling.

Depth of Data Sets

Using multiple data sources is considered one of the strengths of case study design. Creswell (2007) included data collection in his definition of case study research:

Case study research is a qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information (e.g., observations, interviews, audiovisual material, and documents and reports), and reports a case description and case-based themes. (p. 73, bolded italics in original)

Merriam (2009) also included the use of multiple data sets in her description of triangulation, explored in more detail in the “Trustworthiness” section of this paper.

Music education studies. All of the studies examined for this project included multiple data sets. However, some included much “deeper” sets than others. Some interviews were as short as three to four minutes (Gackle & Fung, 2009 with children) or as long as three hours (Standerfer,, 2008 with teachers). See Table 2.0 for depth of data sets.

Description of Analysis

Merriam (2009) recommended a two-part analysis for case studies: within-case analysis (individual case description, including themes), and cross-case analysis (thematic analysis across cases). For single case studies, analysis would consist of bringing together all of the data sets (e.g. interview, observation, artifact) to provide a descriptive, interpretive, or evaluative (depending on the intent of the case study) portrayal of the case. In collective case studies (Creswell, 2007; Merriam, 1998, 2009) where multiple participants who “share a common characteristic or condition” (Merriam, 2009, p. 49) are studied, data are then analyzed across participants to find supporting and contrasting themes. Creswell (2007) recommended a three-part analysis for collective or multiple case studies: within-case analysis (“detailed description of each and themes within the case”), cross-case analysis (thematic analysis across cases), and assertions (“an interpretation of the meanings of the case”) (p. 75).

Music education studies. Oare (2008) devoted a paragraph to describing his data analysis and labeled three categories (teacher, students, and classroom observation), explained that he had 43 codes, and then identified four emergent themes (Social Music Making, Evolving Authenticity, The Balance Between Classical and Folk Music Education, and The Creolization Of Musical Transmission). In Standerfer (2008) there was mention of “cross-case analysis” in the analysis section of the paper but without a clearly defined unit of analysis in the opening of the study it is up to the reader to infer the precise focus of the study. It seems to be common to suggest that analysis was done by coding, categorizing, or drawing out emergent themes. However, the authors often neglect to provide more detail. Conway and Holcomb (2008) state that “The three research questions guided the review of data, and comparisons were made between mentors to gather the collective reactions of the mentor participants” (p. 59) but no other details are provided. Gackle And Fung (2009) stated simply that “The data were analyzed using an inductive approach (Patton, 2002) in which ‘patterns, themes, and categories’ (p. 453) were discovered” (p. 71). They also use the term “grounded theory” with no references to what that is or how it was applied. In contrast, Sindberg (2007) included several paragraphs describing her analysis process, sharing the codes, and reporting on both within case and cross case themes.

Trustworthiness/Validity

Merriam (2009, pp. 213-235) referred to many ways that contribute to trustworthiness and promote validity and reliability including: (a) triangulation, (b) member checks, (c) adequate engagement in data collection, (d) researcher’s position or reflexivity, (e) peer review/examination, (f) audit trail, (g) rich, thick descriptions, and (h) internal validity. We provide a definition of these and then share how the nine studies utilized these tools.

Triangulation. Triangulation may refer to a number of issues: “using multiple investigators, sources of data, or data collection methods to confirm emerging findings” (p. 229). The strength of using multiple investigators who collect and analyze data or triangulating analysts is that more than one person is viewing the same data and findings can be compared and/or discussed. “Triangulation using multiple sources of data means comparing and cross-checking data collected through observations at different times or in different places, or interview data collected from people with different perspectives or from follow-up interviews with the same people” (p. 216). An example of using multiple methods of data collection would be checking what someone said in an interview with your observations or something written in a document.

Member check. Member check, sometimes referred to as respondent validation, is the strategy of soliciting feedback from participants on findings and quotes.

The process involved in member checks is to take your preliminary analysis back to some of the participants and ask whether your interpretation “rings true. Although you may have used different words (it is your interpretation, after all, but derived directly from their experience), participants should be able to recognize their experience in your interpretation or suggest some fine-tuning to better capture their perspectives. (Merriam, 2009, p. 217)

Adequate engagement in data collection. The purpose of adequate engagement in data collection is to collect as much data as it takes to get as close as possible to participants’ understanding of a phenomenon. The data collection should feel saturated, meaning that you begin to see and hear the same things over again and no new information surfaces. In addition: “Adequate time spent collecting data should also be coupled with purposefully looking for variation in the understanding of the phenomenon” (Merriam, p. 219).

Researcher’s position or reflexivity. Case studies “try to capture the wholeness, the essence of what they are studying” and the researcher has “no choice but to merge subjective with objective, personal with general, the meticulously descriptive with the interpersonal” (Stake, 1995a, p. 32). Stake wrote that the researcher is an interpretative tool whose experience becomes a lens through which to view, analyze, and interpret the data (pp. 34-35). Since qualitative methods depend on the researcher’s subjectivity, Merriam (1998) suggested that the researchers explore and explicitly describe their research biases, as their views and judgments become a research tool with which to analyze and interpret the data (p. 205). In Merriam (2009), she defined ‘researcher’s position or reflexivity’ as, “Critical self-reflection by the researcher regarding assumptions, worldview, biases, theoretical orientation, and relationship to the study that may affect the investigation” (p. 229).

Peer review. Although Merriam (2009) acknowledges that this may be already established, as with thesis, dissertation, or peer-reviewed journal committees, there are examples of requesting review from a colleague. Whether the colleague is familiar with the topic or not, “a thorough peer review would involve asking a colleague to scan some of the raw data and assess whether the findings are plausible based on the data” (p. 220).

Audit trail. Merriam (2009) described an audit trail as being, “a detailed account of the methods, procedures, and decision points in carrying out the study” (p. 229). It is important for case study researchers to provide as much detail as possible regarding all aspects of the research.

Rich, thick description. Merriam (2009) wrote:

Today, when rich, thick description is used as a strategy to enable transferability, it refers to a description of the setting and participants of the study, as well as a detailed description of the findings with adequate evidence presented in the form of quotes from participant interviews, field notes, and documents. (p. 227)

Internal validity. Merriam (1998, 2009) referred to internal validity, which addresses the match between the research findings and reality.

One of the assumptions underlying qualitative research is that reality is holistic, multidimensional, and ever-changing; it is not a single, fixed, objective phenomenon waiting to be discovered, observed, and measured as in quantitative research. Assessing the isomorphism between data collection and the “reality” from which they were derived is thus an inappropriate determination of validity. (2009, p. 213)

Music education studies. Eight of the nine studies reviewed included sections addressing trustworthiness, although not all of them labeled the section of the paper as such. Gackle and Fung (2009) do not address any of these issues. Triangulation was mentioned by Conway and Holcomb (2008) and reference was made to both data collection as well as “data analysis triangulation” (p. 59). Hourigan mentions “data collection triangulation” (p. 157) and Chaffin (2009) mentions triangulation as well.

Oare (2008) included a paragraph about member checks with all participants and another paragraph labeled “Researcher’s Lens” which we interpret as “researcher’s position or reflexivity.” Standerfer (2007) gestured to trustworthiness by writing that a member check was conducted but this was the only discussion of trustworthiness in this paper. Chaffin (2009) and Hourigan (2009) made a brief mention of member checks as well as triangulation.

Sindberg (2007) mentioned reflexivity as well as an external auditor. Hourigan (2009) mentioned having a colleague review the coding process which would be considered a “peer review” although he did not label it that way. Conway and Holcomb (2008) discussed length of time in data collection as well as researcher expertise as strategies for strengthening “Analysis, Trustworthiness, and Validity” (p. 58). Conway, Eros, Pellegrino and West (2010) stated: “The primary techniques used to address the trustworthiness (validity) of this study were data collection triangulation, data analysis triangulation, member checking, and attention to investigator expertise (Patton, 2002)” (p. 265). They then include three paragraphs defining these strategies and stating how they were specifically used in that investigation.

Blended Designs

Merriam (2009) wrote that it is the unit of analysis that determines whether a study is a case study, but that other types of studies can be combined with case study (p. 42). The blending of approaches still retains case study’s emphasis on the unit of analysis but incorporates secondary analytical methods. For example, case studies are sometimes blended with ethnography, phenomenology, and/or narrative inquiry. Ethnography describes the culture of a particular group being studied in depth and has its roots in sociology. Phenomenology describes the essences and meanings of a phenomenon as experienced by people in their everyday lives and is based in philosophy. Narrative describes people’s stories and is considered biographical and psychological.

Music education studies. It seems that half of these researchers employed blended designs (Abramo, 2011; Conway & Holcomb, 2008; Conway et al., 2010; Hourigan, 2009; Sindberg, 2007). For example, Conway and Holcomb (2008) stated: “In considering the mentor program as a case, we drew from case study methodology (Merriam, 1998) as well as general principles of phenomenology in research. Within phenomenology we approached this study from the lens of heuristic inquiry. According to Patton (2002), “Heuristics is a form of phenomenological inquiry that brings to the fore the personal experience and insights of the researcher” (p. 107). This example addresses much of the criteria outlined in this paper. The authors provide a citation (Merriam, 1998) for the case study design. They suggest a blending with phenomenology and they state and describe heuristic inquiry as the theoretical framework. They define the unit of analysis and later in the paper discuss the sampling strategy employed.

Sindberg (2007) stated: “This was a collective case study. I also employed ethnographic strategies through the setting of the study and phenomenological strategies through the examination of a particular phenomenon” (p. 29). Although there is not much written on the subject of blending designs, it seems to us that describing the different aspects of each design being drawn from lends to the rigor of the study. As it is in this Sindberg example, the reader is left questioning which ethnographic strategies were used, although she did specify using one phenomenological strategy: “Epoche (Moustakas, 1994) as a strategy to separate my teacher (insider) identity from my researcher identity” (p. 30).

Based on Merriam (2009), we suggest that authors who choose to blend designs with case study consider including the following elements: (a) clearly define the unit of analysis and all case study design elements used, (b) incorporate the focus of the second lens, (c) describe the benefits of using a blended design for this study, and (d) describe which elements of the second lens’s analytical methods were used as well as any other features that were incorporated into the study.

Conclusions and Lessons Learned

In the effort to be cautious in our discussion of case studies we must also be mindful that no definitions are static and that just because an author does not state “case study” as a design does not mean that a case study was not conducted. Flexibility and creativity are hallmarks of qualitative research and we do not want to trap case study in a box defined by Creswell, Merriam, Stake, Yin, or anyone. However, being as explicit as possible does lend to rigor and trustworthiness.

One question researchers and editorial review boards must begin to answer is whether case study research in what authors have referred to as “blended designs” indicates a methodology or a mechanism for reporting findings. For instance, one might study a particular culture, collect qualitative data, and present the findings in the form of a case study. Would that make the study an ethnography or a case study? Or perhaps an ethnographic case study? Or perhaps a qualitative study that presents findings through an ethnographic lens in the form of a case study? We suggest that authors who use blended designs make clear which aspects of each design are being used, including defining the analysis process. The other important feature in case study methodology is to clearly define the unit of analysis.

The profession should also examine what differentiates a single case study from a multiple case study. If one was to present a single case study of a particular culture by drawing conclusions from engaging with multiple participants within that culture, would that be considered a single case study or a multiple case study? The initial answer might be that it would be a multiple case study since it considered multiple individuals within that culture to create a bounded system: the particular culture of the group. But then what would a single case study of a particular culture look like? Are we to infer by the distinction between single and multiple case studies that constructs such as cultures can only be presented as a multiple case study? We suggest that the answer to this question lies in the type of case study being used, which is tied to the unit of analysis as well as the analysis and reporting of the study.

Key sources on case study disagree about the unit of analysis. Yin wrote that holistic designs have a single unit of analysis whereas embedded designs have multiple units of analysis and it is possible to have single holistic case studies, single embedded case studies, multiple holistic case studies, or multiple embedded case study designs (which have the advantage of replication). However, Merriam’s interpretation is that all case studies have one unit of analysis and it is the intent of how the researcher analyzes and reports the study which differentiates them into three categories: descriptive, interpretive, and evaluative. Creswell (2007) wrote about case studies as having a single unit of analysis and distinguished between three types: single instrumental case studies (“the researcher focuses on an issue or concern, an then selects one bounded case to illustrate this issue” (p. 74), collective or multiple case studies (selected to examine and better understand the one issue or concern), and intrinsic case studies [focuses “on the case itself (e.g., evaluating a program, or studying a student having difficulty…) because the case presents an unusual or unique situation” (p. 74).]

This analysis of the use of the word case study and our careful examination of the case study design literature leads us to suggest that researchers in music education should be cautious and intentional in their use of the term “case study.” “Case study” may be used to discuss an overall study design, which includes many defining features. It is also used to represent the unit of study. The term “case study” often appears in relation to a process of analysis and it can also be used to refer to the product created through scholarly inquiry. Since clarity of case study design, including definitions, was the least clear aspect in the music education case study research we reviewed, we suggest that it would be helpful to the reader if the author provides citations to case study scholars to clarify which use of the term “case study” is being employed in a particular context.

To summarize, we suggest that researchers who are conducting qualitative case studies (a) clarify what kind of case study design they are employing and include citations and/or quotes to make this clear; (b) identify and define the single unit of analysis for their study, or, in the case of embedded designs (Yin, 2009), the units of analysis; (c) consider including a theoretical framework in addition to the related literature section; (d) provide a discussion of purposeful sampling procedures used to choose/identify possible participant; (e) collect multiple forms of data, such as interviews, observations, background surveys, documents/artifacts, journals, audiovisual material, etc., (f) describe the analysis process and include discussion about within-case analysis, cross-case analysis, and/or assertions; and (g) describe multiple techniques used to contribute to trustworthiness or credibility (i.e. data triangulation, analyst triangulation, reflexive triangulation, member checks, adequate engagement in data collection, researcher’s position or reflexivity, peer review/examination, audit trail, rich, thick descriptions, and/or internal validity.) In addition, if using a blended design, we suggest that researchers identify the unit of analysis and then clarify which aspects of each design are being employed.

In closing we must reiterate that our examination of music education case studies in this article was not meant to be critical of the studies shared but to highlight for music educators the need for caution in the choice of terms. Readers are encouraged to continue their study of the use of case study. We conclude with a quote from a new source on the topic by Barrett (2014):

For all of the reasons outlined at the beginning of this chapter, case study research has a firm foothold in music education. Yet for its prevalence, the uneven quality of case study reports call our attention to the need for more rigor in design and analysis, attention to the analytical path used to draw inferences from the data, and especially the more sophisticated interplay between cases and theoretical frameworks. (p. 130)

References

Abrahams, F., & Head, P. (2005). Case studies in music education (2nd ed.). Chicago: GIA Publications.

Abramo, J. (2011). Gender differences of popular music production in secondary schools.

Journal of Research in Music Education, 59 (1), 21-43.

Atterbury, B. W., & Richardson, C. P. (1995). The experience of teaching general music. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bailey, R. M. (2000). Visiting the music classroom through the use of the case method in the preparaton of senior-level music teacher education students: A study of reflective judgment. Unpublished D.M.E., University of Cincinnati 61(07), 2639, United States -- Ohio.

Bresler, L. (1995). Ethnography, phenomenology and action research in music education.

Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning, 6 (3), 4-16.

Brinson, B. A. (1996). Choral music: Methods and materials. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Group.

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education (1995). Special issue:

Qualitative methodologies in music education research conference. Bulletin of the

Council for Research in Music Education, 123.

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education (1996). Special issue:

Qualitative methodologies in music education research conference II. Bulletin of the

Council for Research in Music Education, 130.

Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education (1997). Special issue:

Qualitative methodologies in music education research conference II. Bulletin of the

Council for Research in Music Education, 131.

Cain, T. (2008). The characteristics of action research in music education. British Journal of

Music Education, 25 (3), 283-213.

Chaffin, C. (2009). Perceptions of instrumental music teachers regarding the development

of effective rehearsal techniques. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 181, 21-36.

Conway, C. (1997). The development of a casebook for use in instrumental music education methods courses. Columbia University Teachers College Dissertation Abstracts International, 58(9), 3452.

Conway, C. M. (1999a). The case method and music teacher education. Update - Applications of Research in Music Education, 17(2), 20-26.

Conway, C. M. (1999b). The development of teacher cases for instrumental music methods courses. Journal of Research in Music Education, 47(4), 343-356.

Conway, C. M. (2003). The use of story and narrative inquiry in music teacher education

research. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 12 (2), 29-39.

Conway, C. M., Eros, J., Pellegrino, K., & West, C. (2010). Life as an instrumental music

education student: Tensions and solutions. Journal of Research in Music Education, 58 (3), 260-275.

Conway, C. M., & Holcomb, A. (2008). Perceptions of experienced music teachers regarding

their work as music mentors. Journal of Research in Music Education, 56 (1), 55-6.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five

approaches. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Gackle, L., & Fung, C. V. (2009). Bringing the East to the West: A case study in teaching

Chinese choral music to a youth choir in the United States. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 182, 65-78.

Gall, M.D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational research: An introduction (8th

Ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Hourigan, R. (2006). The use of the case method to promote reflective thinking in music teacher education. Update - Applications of Research in Music Education, 24(2), 33-44.

Hourigan, R. (2009). Preservice music teachers’ perceptions of a fieldwork experience in a

special needs classroom. Journal of Research in Music Education, 57 (2), 152-168.

Krueger, P. J. (1987). Ethnographic research methodology in music education. Journal of

Research in Music Education. 35 (2), 69-77.

Lane, J. (2011). A descriptive analysis of qualitative research published in two eminent music

education research journals. Bulletin for the Council of Research in Music Education,

188, 65-76.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lind, V. R. (2001). Designing case studies for use in teacher education. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 10(2), 7-13.

Madsen, C. K., & Hancock, C. P. (2002). Support for music education: A case study of

issues concerning teaching retention and attrition. Journal of Research in Music

Education, 50, 6-18.

Matsunobu, K. (2011). Spirituality as a universal experience of music: A case study of North

American’s approaches to Japanese music. Journal of Research in Music Education, 59

(3), 273-290.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Merriam, S. B., (2009). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications.

Oare, S. (2008). The Chelsea House Orchestra: A case study of a non-traditional school

instrumental ensemble. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 177, 63-78. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40319452

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd. Ed.). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Richardson, C. P. (1997). Using case studies in the methods classroom. Music Educators Journal, 84(2), 17-21, 50.

Sindberg, L. (2007). Comprehensive musicianship through performance (CMP) in the lived

experience of students. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 174, 25-43. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40319477

Stake, R. E. (1995a). The art of case study research. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage

Publications.

Stake, R. E. (1995b). Case study: Composition and performance. Bulletin of the Council

for Research in Music Education, 122, 31-44.

Stake, R. E., (2010). Qualitative research: Studying how things work. New York: Guilford.

Standerfer. S (2008). Learning from the National Board for Professional Teacher Certification

(NBPTS) in music. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 176, 77-??)

Thaller, G., Finfrock, B., & Bononi, R. (1993). The development of cases for use in music teacher preparation. Unpublished manuscript, University of Cincinnati.

West, C (in press). First generation mixed methods designs in music education research: Establishing an initial schematic. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design methods. (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oakes, CA:

Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design methods. (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oakes, CA:

Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage Publications.

[1] A newer edition of Yin is now available in Yin 2009.

[2] A newer edition of Stake is now available in Stake 2010.

[3] Although case study researchers examine one particular phenomenon, phenomenological researchers (a) examine the essences and meanings of a phenomenon as experienced by people in their everyday lives and encourage “a certain attentive awareness to the details and seemingly trivial dimensions of our everyday educational lives” (van Manen, 1990, p. 18); (b) collects and analyzes data that are not only from participants, but are also “the investigator’s firsthand experience of the phenomenon” (Merriam, 1998, p. 12); and (c) describes “what all participants have in common as they experience a phenomenon” (Creswell, 2007, p. 58). As with all methods, phenomenology has specific analysis procedures associated with it, such as Epoche, or bracketing (Moustakas, 1994, p. 33), and specific multistep analysis procedures as described by Moustakas (1994, 120-154).